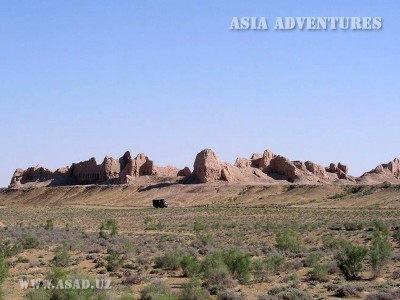

The Khoresm civilisation sprang up in about the mid-2nd millennium BC in the lower course of the Amudarya (a territory including today"s Republic of Karakalpakstan and some portion of the present-day Turkmenistan), later than ancient Egypt and Babylon, which had been developing in similar natural conditions. Like today, the great Oxus river (that was how the Europeans used to call the Amudarya) fed by glaciers high in the Pamir Mountains was carrying its waters a thousand kilometres away to form in its lower stream a fertile oasis bordered by the Kyzylkum desert. The seasonal irrigation connected with the river flooding, the Aral Sea and its shores rich in fish and game and the vast pastures around made this land the cradle of a unique culture, which gave us a number of grandiose lost cities and imposing fortresses.

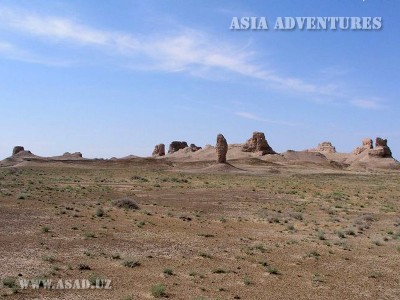

There are over 200 archaeological sites situated in Ellikala region of Karakalpakstan, the most outstanding of which, such as Toprak-kala or Ayaz-kala, continue to surprise both the tourists arriving to see them and the archaeologist studying these architectural monuments. The total number of ancient fortresses situated in the territory once occupied by ancient Khoresm is about 1,000. We know very little about most of them, as they are situated away from roads, amidst impassable dunes and salt marshes, in the bed of rivers that dried long ago.

The most interesting of the fortresses that have remained to our days are:

- Ayaz-kala;

- Toprak-kala;

- Kyzyl-kala;

- Chalpyk-kala;

- Jambas-kala;

- Dzhanpik-kala;

- Kyrkkyz-kala;

- Koy-kyrglan-kala;

- и др.

The ruins of the fortresses are full of mysteries, the most challenging of which is how such large settlements could be placed amidst a lifeless desert, far away from the fertile lands of the Amudarya intersected since the 5th century with a network of irrigation canals. This can be explained by large numbers of nomadic tribes surrounding Khoresm, with whom in time of peace the Khoresmians exchanged grain and other goods. However, to maintain peace in the country the borders had to be protected from those very nomads.

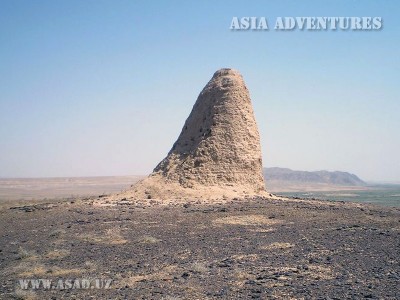

Another explanation is that the Amudarya, apart from water and fertile silt, brought death and chaos to the people. The river’s unruly course, which often changes direction in our days, used to cause terrible floods in the old times. This made the people of Khoresm organise their towns on elevations among the deserts sands, the high town walls protecting the rulers’ palaces, barracks, temples of worshippers of fire and sun and artisans’ quarters from enemies and water.

In the course of many centuries the people of Khoresm followed the same principle of fortress construction. The river sand was used in the foundation of a building, as it did not absorb moisture but could absorb vibration caused by earthquakes. The walls were made of large-sized square mud brick, which today remains as strong and can still be used in construction. Almost every brick has a special sign, tamga, cut on it. We do not quite know about the purpose of these marks, whether they were the signs of the craftsmen who produced the bricks or the family emblems of royal families. Natural clay was used in the construction as a cohesive element, making even the arches in the inner walls strong enough to bear the weight of the construction. Pieces of rock wedged between the bricks of the arches made their structure even stronger. As this region has always been poor in trees, timber was rarely used in construction. However, as we can see, the ancient builders managed quite well without it. It is remarkable that the architects of the first centuries AD created a water supply system conveying water from a nearby canal inside one of the fortresses. Baked ceramic pipes, 50-60 cm in diameter, were being used for many years.

The ancient builders worked quite rapidly, completing a fortress for some two or three months. They knew their profession perfectly well and were quite aware of the properties different building materials had. Whether it was due to the excellent material that the masters used in the construction or to the ancient architects knowing some long forgotten secrets of production of strong mud blocks and bricks, we do not know. But the walls of fortresses built of those bricks have passed the test of time, withstood winds, rains and strong desert heat, and survived the attacks of Qutaybah, an Arab general who captured Khoresm in 712, and, later, the Mongol invasion. Many of the ancient fortresses look as if they were left but yesterday. But what is the most surprising is that, despite their magnificence and good state of preservation, most of these fortresses are known to a relatively small group of experts. Perhaps, one of the causes they are in such a good condition is that, situated away from roads, they are hardly reachable without the assistance of local historians.

Centralasia Adventures

+998712544100

Centralasia Adventures

+998712544100